Blacksburg, Virginia

Leonard Currie, architect

Charles Pascoe, builder

Construction 1960-1961

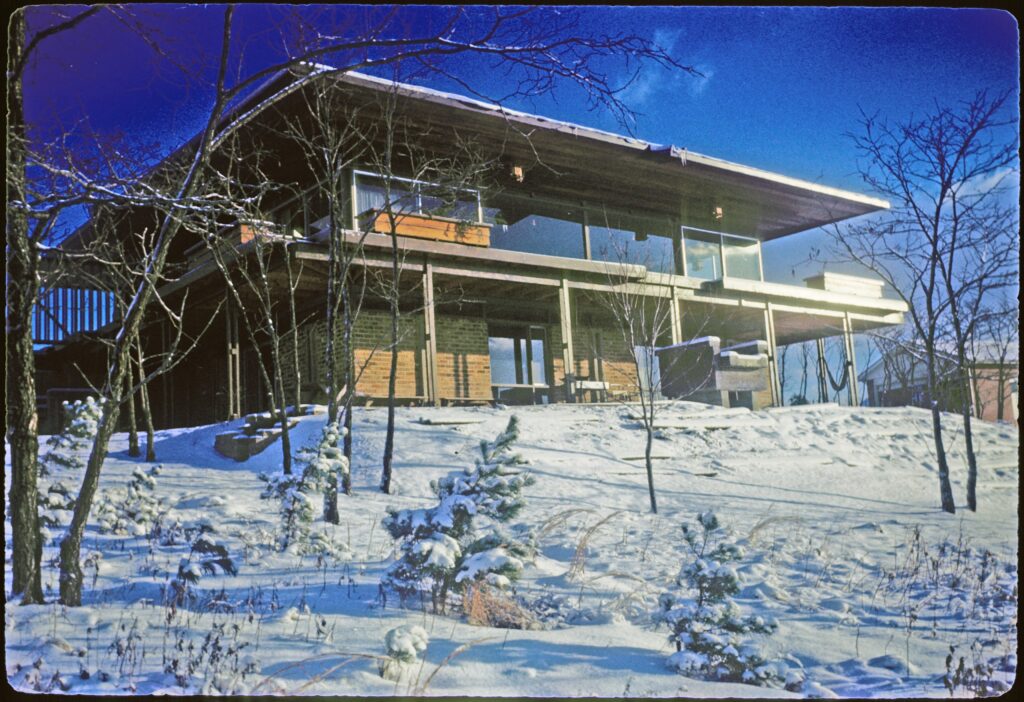

Photo December 1981

Currie arrived at Virginia Tech in 1956 to succeed Clinton Cowgill as head of the Architecture Department. A former student, Jim Ritter, FAIA, remembers that Currie required all freshmen to write an essay on “The Williamsburg Blight”, a reference to the proliferation of faux-Georgian houses being built in Virginia. The home Leonard and Virginia built for their family in Blacksburg was their contribution to moving the Commonwealth past nostalgia for Williamsburg.

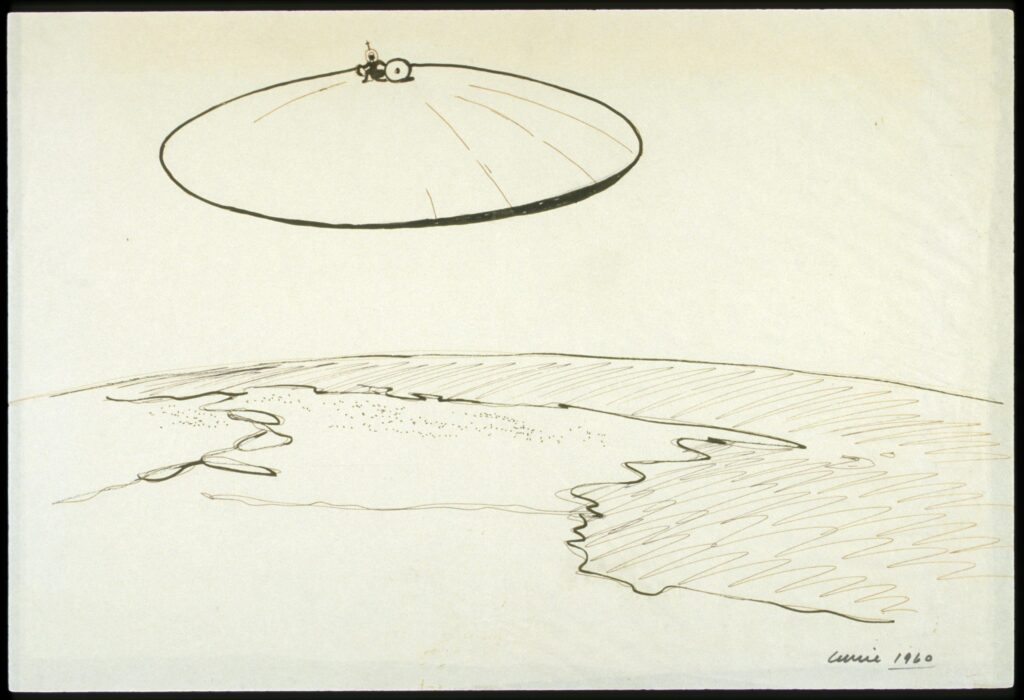

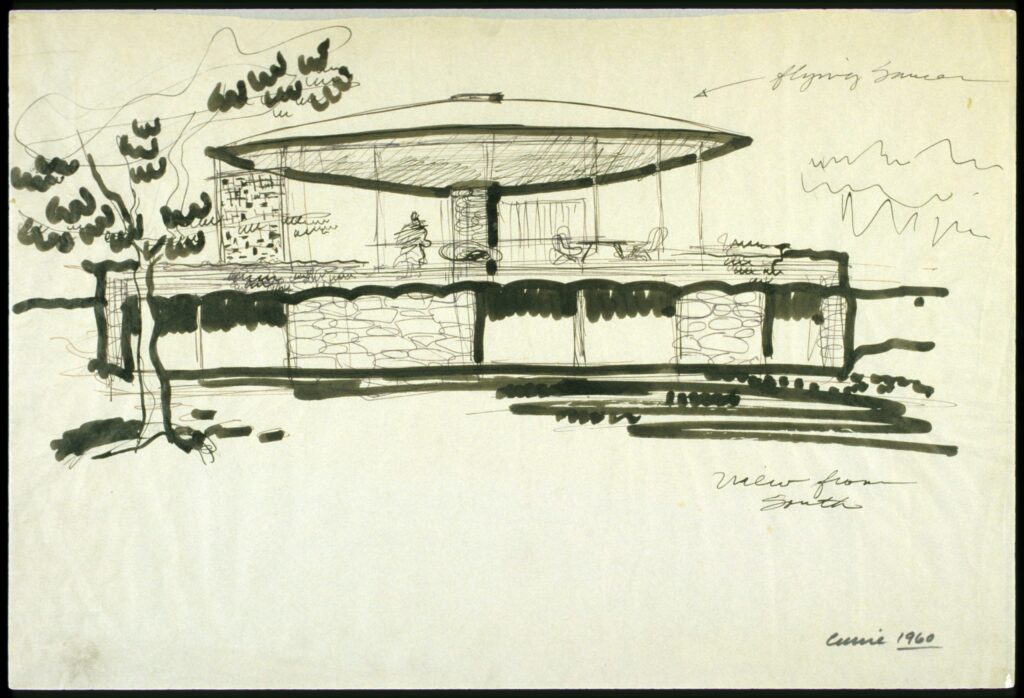

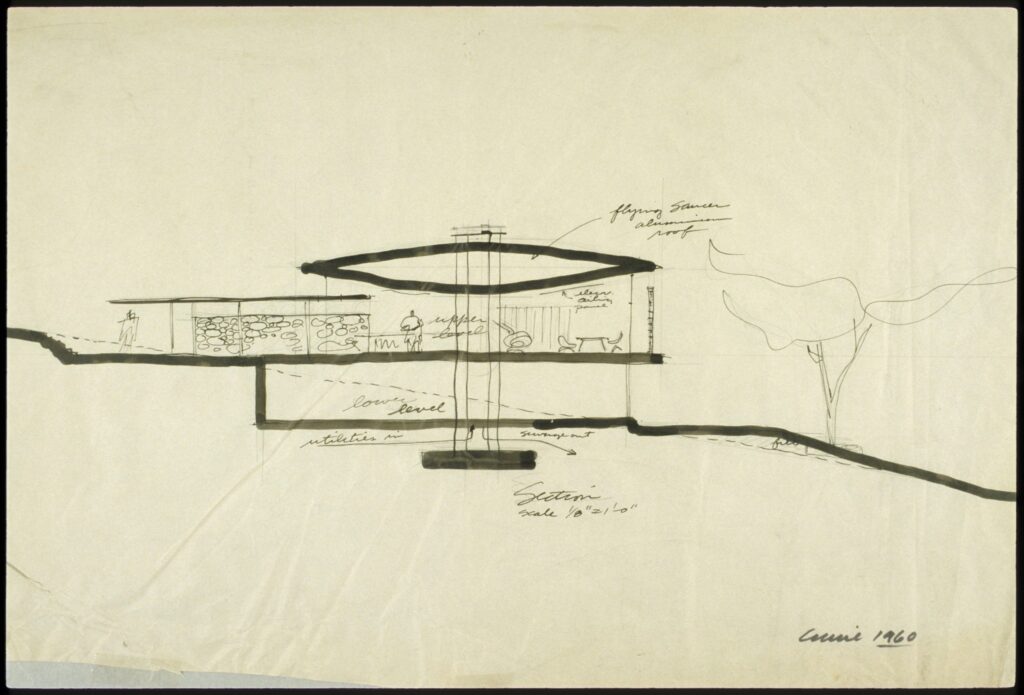

Modernism for Currie was sincere use of methods and materials tailored to the time and place, and also innovation. In Currie House, one of the innovations is the flying saucer roof that hovers overhead.

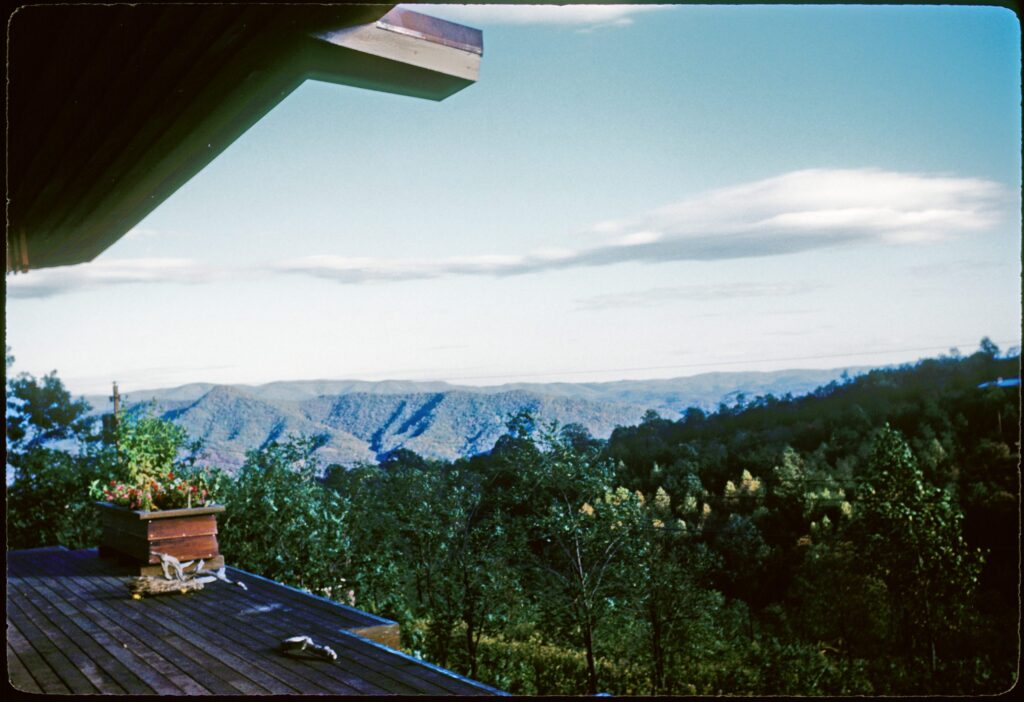

The flying saucer construction is a network of wooden beams that cantilever from a central service core that supports them. The structure allows for an expanse of glass that offers a view of the mountains. Clerestory windows and overhanging eaves enhance an illusion of aerodynamic lift.

The house is designed for passive heating and cooling. The glass wall on the south side, shown below, is oriented toward the sun of the winter solstice so the low winter sun shines through the windows for much of the day. In the summer, the large overhang of the eaves provides shade from the higher sun. On the north side of the house, which faces the street, only the upper floor is exposed to the climate. Curtains inside the glass walls provide insulation and privacy.

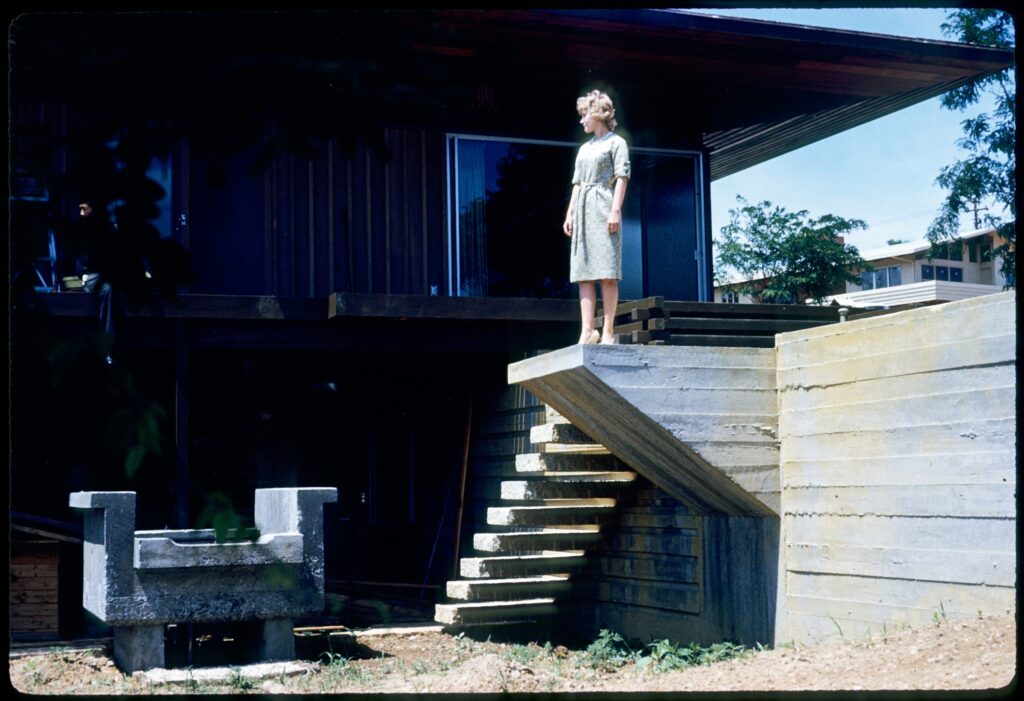

Virginia Currie designed the interior stairs, which she called the Breuer stairs, and the cantilevered stairs outside. The granite for the outside stairs is from Mt. Airy quarry in North Carolina near the Virginia border. The steps are reminiscent of granite steps projecting from walls at Machu Picchu, which Virginia had visited with Leonard.

Currie disapproved of sentimental imitation of historic styles, but by no means jettisoned history or a regional sensibility. He built his house for the Appalachian Highlands, integrating it into the hillside and using handmade bricks salvaged from the demolition of faculty housing on the Virginia Tech campus. Later, in Chicago, he rehabilitated a nineteenth century house and incorporated items from the demolition of other houses. He incorporated additional salvage from Chicago in the second house he built in Blacksburg after he retired from the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Currie’s interest in regional vernacular comes through in a telephonic symposium on regional architecture in the Americas, held in January, 1959, while Currie was conceiving the house. Panelists included Marcel Breuer, Alvaro Ortega, and I.M. Pei, among others — “Transcript of an Inter-American Architectural Symposium,” Arts & Architecture, vol. 76, no. 4, April 1959, pp. 12-14, 30-31.

Currie House won an American Institute of Architects (AIA) First Honor Homes for Better Living award in 1963 and a Virginia AIA Test of Time Award in 1983. The house was placed on Virginia Landmarks Register and the National Register of Historic Places in 1994.

For more information about Currie House I see:

“Best in design from 1963 Homes for Better Living program: A simple plan embellished with warm details and materials.” House & Home, vol. 24, no. 1, July 1963, pp. 86-7.

Sarah Shields Driggs, “Currie House, Montgomery County, Virginia.” National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 12 August 1993.

“Virginia Architects Honor Blacksburg Residence, Test of Time Award.” Virginia Record, vol. 105, no 2, March-April 1983, p. 18.